Sprinting 101 for Strength and Conditioning Coaches – Part 1

Speed & Agility | Sports PerformanceABOUT THE AUTHOR

Derek Hansen

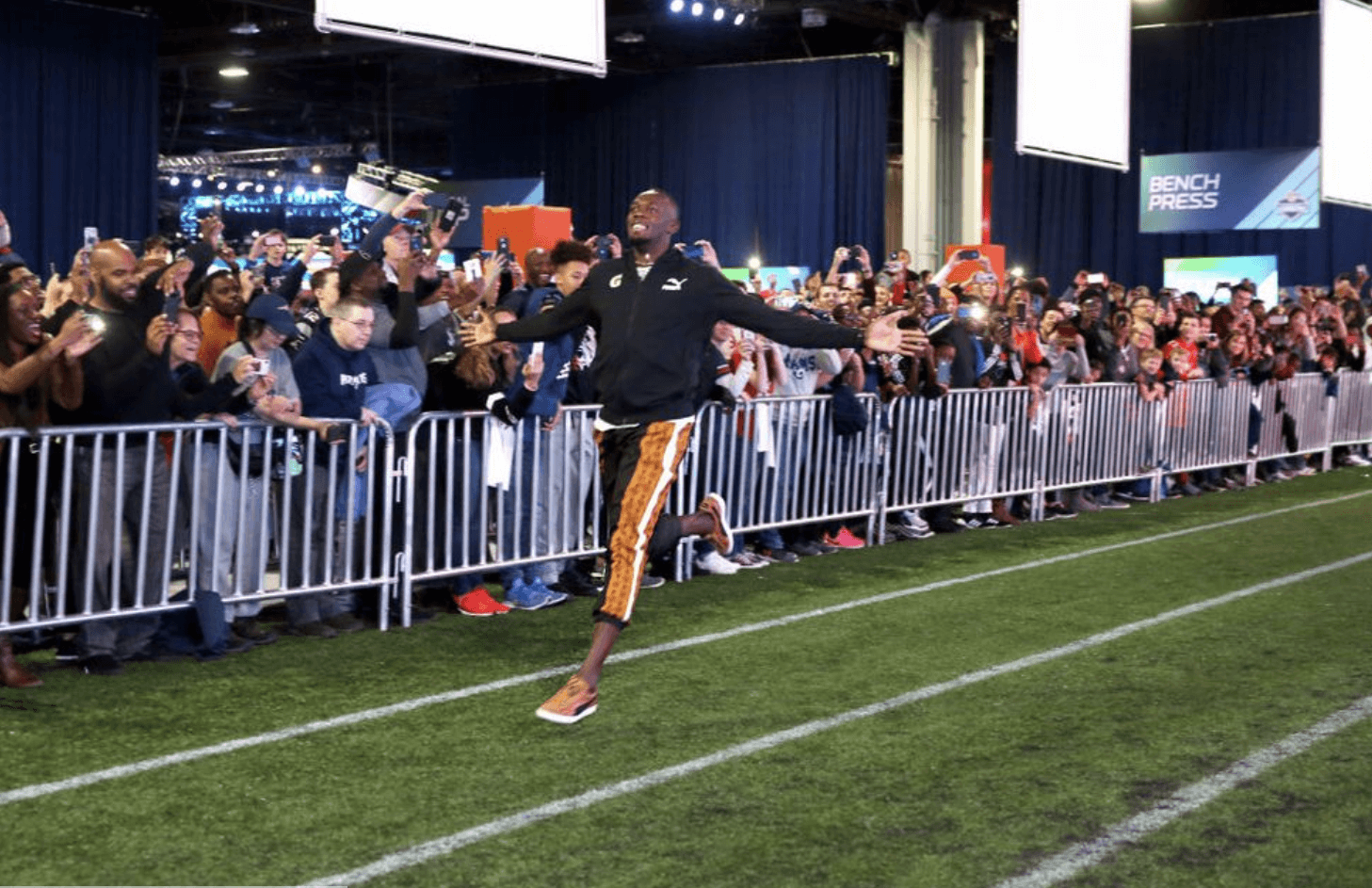

Running is one of the most elemental things we can do as athletes or, for that matter, as human beings. But just because the instinct is hard-wired into our DNA, it doesn’t mean that it’s something you can just put into your programming willy-nilly, particularly when it comes to sprinting. This is because it’s a highly skilled activity that, if done incorrectly, can lead to injury and, if combined with too much Olympic lifting or other high-intensity work, contribute to overload and burnout.

That said, sprint work properly dosed can increase speed and power for every athlete, as well as reducing ground contact time, improving locomotion, and delivering a whole host of other benefits. To find out how to add sprint work to your coaching toolbox, we called in Derek M. Hansen, a Vancouver-based international sports performance consultant who apprenticed under legendary sprint coach Charlie Francis and works with pro athletes and teams in everything from the NBA to the NFL to, logically enough, track and field. In this first of two installments, Derek shares his pointers on technique, identifies common pitfalls to avoid, and offers suggestions on the choice of running surface and shoes.

Outside of simply getting faster, what advantages can sprinting offer non-track athletes?

When I work with NFL, NBA, or MLS teams, I make them think about the times when they have to sprint in their sport to show them how applicable it is. For football players, that might be running to catch a pass or prevent a reception. So what we do on the track obviously transfers directly to their actual performance. We see that their locomotion usually improves, and so does their jumping, elasticity, and running economy. There’s a crossover effect to anything that requires high CNS activity. Sprinting seems to transfer more than other training activities. Often we see coaches focus on trying to get someone’s squat max up, say from 400 to 500 pounds. But while being stronger is beneficial, it can sometimes have drawbacks, like getting stiffer. Whereas with sprinting, unless you’re doing too much, there’s generally positive lateralization.

Even endurance athletes need speed more than they might imagine. The world’s best marathon runners are getting close to breaking the two hour barrier, which means they’re doing 26 miles around 4:40. So they must be able to run one mile in 3:50, sub-50 seconds in the 400, and even a fast final 100 or 200. So a distance runner adding in some sprint work can feed into other things. And if you have an athlete who needs to strip off a little fat, nobody has ever faulted sprinters for their body composition. Getting them out on the track to run some sprints twice a week can help reduce their body fat.

When a team brings you in to consult, what’s the first thing you do?

I’ve got to sit down with the coaching staff and differentiate between a true sprint and merely running. Often you find athletes going longer or slower and this being called “sprinting,” when it isn’t really. So we need to delineate between sprinting and running, acceleration and deceleration, and so on, so we can all agree on what we’re talking about and use the same language with the athletes. From there, I like to focus on some basic technical elements by doing a series of drills. These focus on arm and leg action and posture. I usually start people sprinting at only 80 or 85 percent, even once they think they’ve got the technique down, because they still need to focus on the technical aspect. This could continue for three or four weeks. Just like in weightlifting, how you wouldn’t load someone up with what you thought was their max from the get-go. Instead, you’d do plenty of technique work first and build a technical model. Then you’d have a progression and begin to add weight when they were ready.

For coaches who don’t come from a track and field background, what are some common mistakes you see, and how do you correct these?

One of the things I see a lot is coaches believing that more resistance is better. So you see them having their athletes push or pull heavy sleds and using parachutes, and that’s their focus. They seem to think if they use a band that’s good, and if they could add in a chute, sled, and weight belt they’d really be onto something. But that can have adverse effects, because with resistance, you’re staying on the ground loading and taking longer for your muscles to contract. You also see athletes starting to alter their posture and biomechanics. Sometimes I’ll add in a little resistance, but only after an athlete has got the basics down and can move their body efficiently. And if we do add some load, it will never exceed five to 10 percent on top of their bodyweight.

The same is true of hill work. Some coaches assume that the higher the hill or the steeper the gradient, the better. But when I worked with the Minnesota Vikings to help them build a hill, we ended up with a very mild grade because that’s all the players needed to challenge themselves.

Jamaican sprinters seem to do a lot of their sessions on grass. What are your thoughts on that versus

using a track?

Grass is certainly more forgiving on the joints. But with a track, you can work on speeding reaction times and reducing ground contact because you’re maximizing energy return. One NFL team I work with does a lot on artificial turf, and you can feel it dampening your response time. That can make your tendons stiffen up. So it helps to mix things up. Sometimes you can vary the surface as you move through a periodized plan. Jamaican sprint coaches have their sprinters do most of their volume work on grass early on in the season, and then as they move into the competitive calendar, they start doing more on the track. I have a friend – Mike Hurst – who coaches in Australia. He changes up the surface depending on the time of year because the ground can be baked hard.

If you keep switching up the surfaces, you can emphasize certain traits and vary the stimulus of each session. Planned variability is important because the body adapts to the same stimulus very quickly. If you don’t regularly introduce change, you’ll start to detrain. Choice of surface is just one example of doing a gap analysis, which you need to use continually in coaching. What are your athletes getting too much of? What aren’t they getting enough of? How can you eliminate redundancy? I have to frequently ask myself these questions and then alter my programming based on the answers.

What footwear do you typically recommend for sprinting?

Basketball players typically wear pretty flat shoes, which are good in some ways, but can place more strain on the Achilles tendon. So I often have them wear a shoe with a little more heel-to-toe drop to mix it up a bit and remove undue stress from that area. Soccer and football players do just about everything in cleats, so again, I want them to mix it up a little bit. And most team sports athletes who lift have shoes for the weight room, too. I think you need a range of footwear for different activities. Maybe not quite as many as decathletes, who have to run, vault, jump, and throw, but a range. Sometimes I’ll have athletes sprint in spikes as they allow a quicker reaction time and have unbeatable grip on the track, whereas if we’re training on grass, they might not need them.

When you’re working on mobility after sprinting, what areas do you target?

We do a lot of work around the hips, adductors, and glutes and make sure our athletes are mobile in the lower back. Most restrictions we find on the periphery can usually be traced back to these areas. It’s also a matter of making your strength work dynamic. Isometric holds like planks have a place, but sprinting requires hip and midsection mobility, so you need to introduce range of motion and stability into exercises. Strength and mobility must be interrelated or you’re going to get issues with stiffness, lack of coordination and activation, and so on. Just as with training itself, we try out lots of different stimuli – sending athletes to a PT, massage, static stretches, using rollers, balls, bands, and other tools. It’s best to have variability in your recovery techniques and, as with every other element of coaching, determine what each situation requires.

Check back soon for Part 2.

Are you a better coach after reading this?

More coaches and athletes than ever are reading the TrainHeroic blog, and it’s our mission to support them with useful training & coaching content. If you found this article useful, please take a moment to share it on social media, engage with the author, and link to this article on your own blog or any forums you post on.

Be Your Best,

TrainHeroic Content Team

HEROIC SOCIAL

HEROIC SOCIAL

TRAINING LAB

Access the latest articles, reviews, and case studies from the top strength and conditioning minds in the TH Training Lab